Testing¶

We've slowly been moving parts of our code into files outside of notebooks... but why?

- Reuse – we could copy

my_module.pyand use it in another project if we had need for the functions in there.

- Testability – one nice aspect of free-standing Python scripts is that we can write tests for them, checking that the functions inside are reliable and bug-free.

The Value of Testing¶

By running your code on example inputs (for which you know the right output), you can be more confident that it will do what you expect

Since you may reuse code in other projects, it's smart to test on not just the data for the current project, but any inputs that your code might reasonably have to deal with.

At this point, our directory setup is going to become very important, so let's take a quick detour to talk about it.

I'm going to be working with a project that looks something like this:

advanced-python-datasci/

├── data/

│ ├── adult-census.csv

│ ├── ames.csv

│ ├── ames_raw.csv

│ └── planes.csv

└── notebooks/

├── 01-git.ipynb

├── 02-explore_data.ipynb

├── 03-first_model.ipynb

├── 04-modular_code.ipynb

├── 05-feat_eng.ipynb

├── 06-model_eval.ipynb

├── 07-modularity-pt2.ipynb

├── 08-testing.ipynb

├── 09-ml_lifecycle_mgt.ipynb

└── my_module.py

What's important:

- At the top level, we have folders for

dataandnotebooks my_module.pyis in our notebooks folder

Take a few minutes to make sure your project repository is organized similarly. This will make a big difference in this section!

advanced-python-datasci/

├── data/

│ ├── adult-census.csv

│ ├── ames.csv

│ ├── ames_raw.csv

│ └── planes.csv

└── notebooks/

├── 01-git.ipynb

├── 02-explore_data.ipynb

├── 03-first_model.ipynb

├── 04-modular_code.ipynb

├── 05-feat_eng.ipynb

├── 06-model_eval.ipynb

├── 07-modularity-pt2.ipynb

├── 08-testing.ipynb

├── 09-ml_lifecycle_mgt.ipynb

└── my_module.py

A Minimal Test¶

The easiest way to write a test is in a fresh Python script

Now that our project is organized, we can just create a new file in the

notebooks/folder, calledtests.py- Remember that we can do this in Jupyter with File > New > Text File

- Be sure this file appears in your notebooks folder!

- It's very important that it's in the same place as

my_module.py

- It's very important that it's in the same place as

Add the following code to your script:

import my_module

def test_invocation():

features, target = my_module.get_features_and_target(

csv_file='../data/adult-census.csv',

target_col='class'

)

Discussion

If we were to run this code on its own withpython tests.py, what would happen?

Running Our Test¶

- We're going to invoke our test with pytest, a tool we'll discuss more shortly

- Open a terminal session (in Jupyter, File > New > Terminal)

- Things in the terminal are a bit different here in Windows vs Mac/Linux, so we'll try to help how we can...

Run the below command in a notebook to find out what folder you're currently working in:

import os

os.getcwd()

'/Users/eswan18/Teaching/advanced-python-datasci/notebooks'

Copy that result (including the quotes) and in your terminal, paste it after the cd command.

So in my terminal, I would run:

cd '/Users/eswan18/Teaching/advanced-python-datasci/notebooks'

Now...

- Windows users: run

dir - Mac/Linux users: run

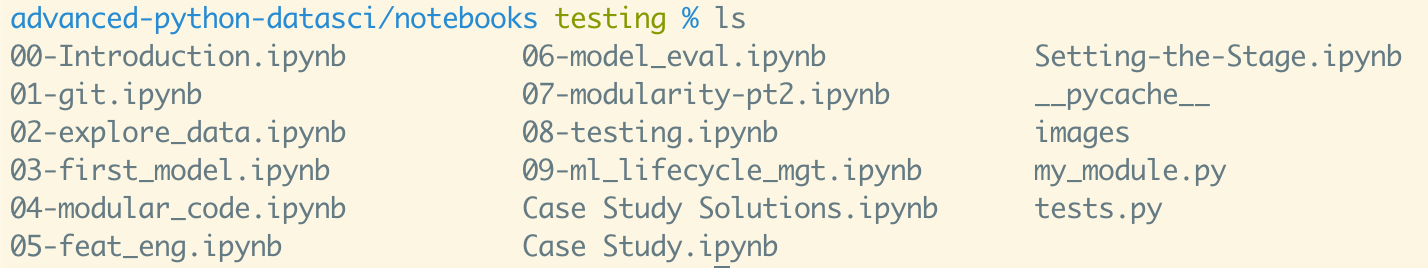

ls

This lists the contents of the folder you're currently inside.

You should see my_module.py and tests.py among the output.

Now, we're almost ready to run our test.

The only thing left is to set up our terminal so that it's using the same Conda environment as our notebooks -- because pytest is installed in that environment.

- If you took the intermediate class with us, we discussed Conda and environments in more detail then.

In the terminal, run

conda activate uc-python

This should add a "uc-python" prefix to your terminal prompt:

Note that your prompt will look quite a bit different from mine; all that matters is the folder name and the "uc-python" prefix.

Now we're ready to run our test!

In your terminal, type:

pytest tests.py

You should see some output appear. The last line should look something like:

============ 1 passed in 0.74s ============

This means that 1 (test) passed and 0 tests failed, and the whole process took 0.74 seconds.

Pytest¶

- Pytest is an automated tool for running sets of tests

- sets of tests are often called test "suites"

- It expects your tests to be in their own files, and each test needs to be a function

- The name of each function must start with

test_, so pytest knows it's a test and not just a regular function.

- The name of each function must start with

Let's look back at our simple test:

import my_module

def test_invocation():

features, target = my_module.get_features_and_target(

csv_file='../data/adult-census.csv',

target_col='class'

)

Note that our function starts with def test_, and pytest is smart enough to run it.

What happens if a test fails? Let's add a bad test just to see.

Add this function to tests.py, below test_invocation.

def test_without_args():

# A test we know will fail because we don't provide arguments

# to the function.

features, target = my_module.get_features_and_target()

Save the file, and then rerun pytest tests.py in your terminal.

============== 1 failed, 1 passed in 0.83s ==============

Our original test still passes, but this one fails!

Above this line, pytest reports exactly what happened that caused it to fail. We got an error:

def test_without_args():

# A test we know will fail because we don't provide arguments

# to the function.

> features, target = my_module.get_features_and_target()

E TypeError: get_features_and_target() missing 2 required positional arguments: 'csv_file' and 'target_col'

tests.py:12: TypeError

What does it mean to "fail"?¶

- If a test function encounters any kind of unexpected error, that counts as a failure to pytest

- Any test that runs without error "passes"

Let's remove our test_without_args test -- it's not something we actually want to verify about our code.

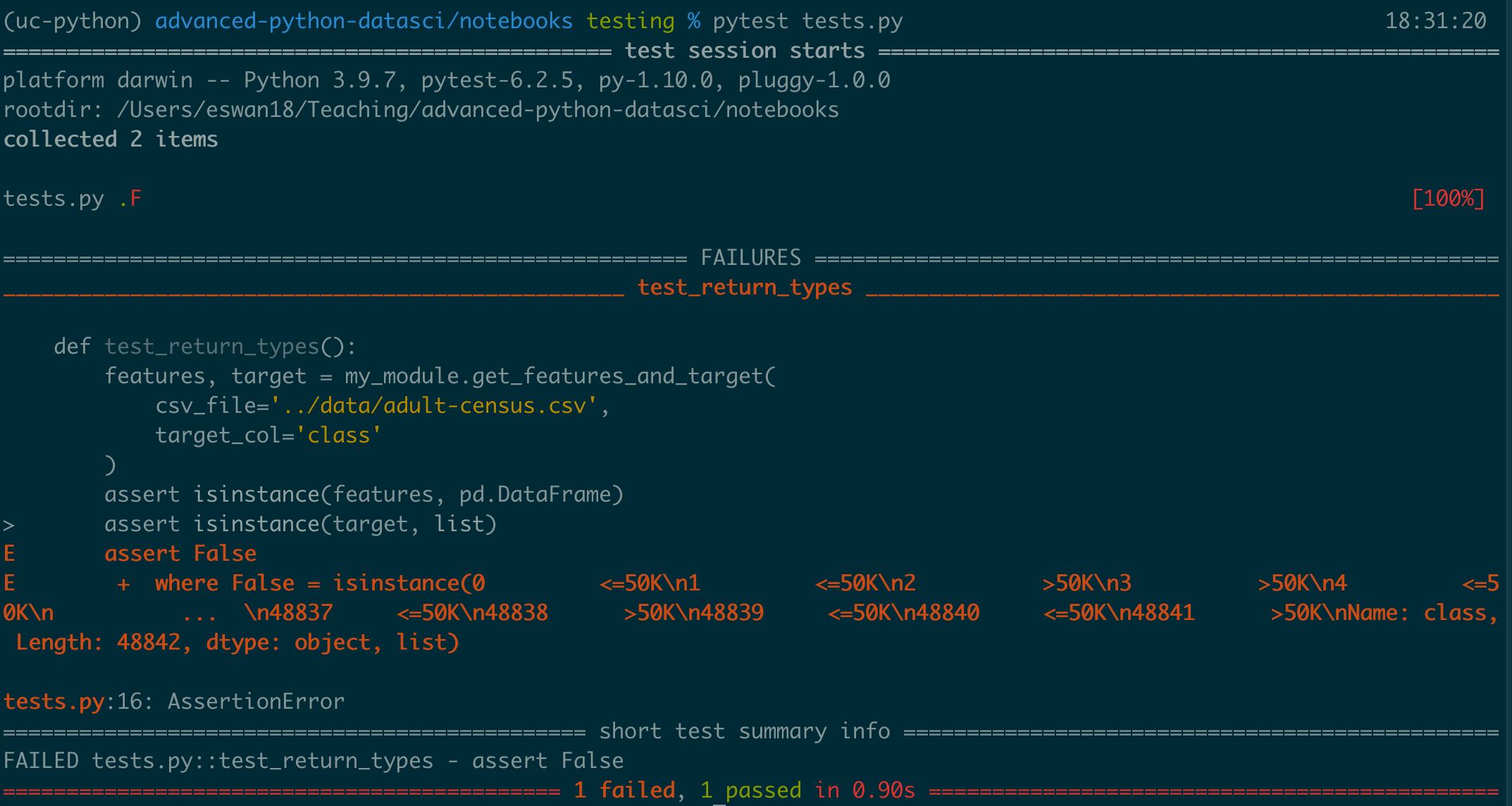

However, one thing we do want to check is that the features and target that are returned from our function are a pandas DataFrame and Series, respectively. Let's add a test for that in its place...

import pandas as pd # You may want to move this import to the top of the file.

def test_return_types():

features, target = my_module.get_features_and_target(

csv_file='../data/adult-census.csv',

target_col='class'

)

assert isinstance(features, pd.DataFrame)

assert isinstance(target, pd.Series)

The we can rerun pytest tests.py

=========== 2 passed in 0.88s ===========

Nice! It looks like our function does indeed return a DataFrame and a Series.

Assert¶

- We used the

assertkeyword to check thatfeatureswas a DataFrame assertis a special Python feature that raises an error if the expression after it isn't True.

assert 3 - 2 == 1

assert 100 > 50

assert 4 * 3 == 11

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- AssertionError Traceback (most recent call last) /var/folders/j3/v1318ng94fvdpq7kzr0hq9kw0000gn/T/ipykernel_72985/55912000.py in <module> ----> 1 assert 4 * 3 == 11 AssertionError:

One common use of assert in tests is to check that a variable contains a certain kind of object:

x = 5

assert isinstance(x, int)

assert isinstance(x, str)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- AssertionError Traceback (most recent call last) /var/folders/j3/v1318ng94fvdpq7kzr0hq9kw0000gn/T/ipykernel_72985/3799747894.py in <module> ----> 1 assert isinstance(x, str) AssertionError:

But you can use assert to check any expression in Python that evaluates True or False.

What would happen if we had expected target to be a list instead?

def test_return_types():

features, target = my_module.get_features_and_target(

csv_file='../data/adult-census.csv',

target_col='class'

)

assert isinstance(features, pd.DataFrame)

assert isinstance(target, list)

These kinds of tests are handy, because we can make sure our functions return the types of things we expect.

Discussion

What other aspects ofget_features_and_target might we want to test?

test_cols_make_sense¶

- If

get_features_and_targetworks as we expect, thetargetshould be a column in the DataFrame, as should each of the columns infeatures. - Here's a test to check that.

- There's some pandas functionality in here that we haven't discussed yet, but it should be clear what's happening.

- Add this test to

tests.pyat the bottom. Make sure you're importingpandassomewhere in the file!

def test_cols_make_sense():

features, target = my_module.get_features_and_target(

csv_file='../data/adult-census.csv',

target_col='class'

)

# Load the data ourselves so we can double-check the columns

df = pd.read_csv('../data/adult-census.csv')

assert target.name in df.columns

# Use a list comprehension to check all the feature columns

assert all([feature_col in df.columns for feature_col in features])

============= 3 passed in 0.97s =============

Whoo!

get_features_and_target looks pretty reliable;

I feel more comfortable using it across modeling projects to load data and split it into a target and a DataFrame of numeric features.

If I were planning to use it more, though, there are some other things I might think about testing:

- The number of elements in

targetshould match the number of rows in the original data, as should the number of rows infeatures. - All of the columns in

featuresshould be numeric. - All numeric columns in the input file should be present either in

featuresortarget - The name of the

targetseries should match thetarget_colargument that we passed into the function.

But for the sake of time, we're going to stop at these three tests for the function.

Parametrization¶

- Another way we could check the robustness of

get_features_and_targetis by making sure that it works on multiple data sets, not just the adult census data. - We could write entirely new tests for this...

def test_return_types_census():

features, target = my_module.get_features_and_target(

csv_file='../data/adult-census.csv',

target_col='class'

)

assert isinstance(features, pd.DataFrame)

assert isinstance(target, pd.Series)

def test_return_types_ames():

features, target = my_module.get_features_and_target(

csv_file='../data/ames.csv',

target_col='Sale_Price'

)

assert isinstance(features, pd.DataFrame)

assert isinstance(target, pd.Series)

But this is very duplicative. There has to be a better way!

Indeed, there is: it's parametrization.

To parametrize a test is to give it multiple inputs.

import pytest

@pytest.mark.parametrize(

'csv,target',

[

('../data/adult-census.csv', 'class'),

('../data/ames.csv', 'Sale_Price')

]

)

def test_return_types(csv, target):

features, target = my_module.get_features_and_target(

csv_file=csv,

target_col=target

)

assert isinstance(features, pd.DataFrame)

assert isinstance(target, pd.Series)

Notice that our inputs are parameters to our test function.

@pytest.mark.parametrize takes a list of tuples to be passed to our test, along with the arguments they correspond to ('csv,target').

This syntax may look complicated initially, but it's easy enough to copy, paste, and modify for each test you want to parametrize.

=========== 4 passed in 0.93s ==========

This test should pass, and notice that we went from having 3 tests to 4 -- because one of them is being run twice, once for each parameter.

For the sake of time, we're not going to parametrize all of our tests, but in a larger, production-grade test suite, that would be worth doing.

Expecting Exceptions¶

One mark of good code is that it emits sensible errors

For example, if we pass in the wrong kinds of objects to our function, it should give us an error that points us in the right direction...

features, target = my_module.get_features_and_target(

csv_file=['../data/ames.csv'], # notice that we're passing a list here

target_col='Sale_Price'

)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- ValueError Traceback (most recent call last) /var/folders/j3/v1318ng94fvdpq7kzr0hq9kw0000gn/T/ipykernel_72985/3089255148.py in <module> ----> 1 features, target = my_module.get_features_and_target( 2 csv_file=['../data/ames.csv'], # notice that we're passing a list here 3 target_col='Sale_Price' 4 ) ~/Teaching/advanced-python-datasci/notebooks/my_module.py in get_features_and_target(csv_file, target_col) 7 '''Split a CSV into a DF of numeric features and a target column.''' 8 ----> 9 adult_census = pd.read_csv(csv_file) 10 11 raw_features = adult_census.drop(columns=target_col) ~/anaconda3/envs/uc-python/lib/python3.9/site-packages/pandas/util/_decorators.py in wrapper(*args, **kwargs) 309 stacklevel=stacklevel, 310 ) --> 311 return func(*args, **kwargs) 312 313 return wrapper ~/anaconda3/envs/uc-python/lib/python3.9/site-packages/pandas/io/parsers/readers.py in read_csv(filepath_or_buffer, sep, delimiter, header, names, index_col, usecols, squeeze, prefix, mangle_dupe_cols, dtype, engine, converters, true_values, false_values, skipinitialspace, skiprows, skipfooter, nrows, na_values, keep_default_na, na_filter, verbose, skip_blank_lines, parse_dates, infer_datetime_format, keep_date_col, date_parser, dayfirst, cache_dates, iterator, chunksize, compression, thousands, decimal, lineterminator, quotechar, quoting, doublequote, escapechar, comment, encoding, encoding_errors, dialect, error_bad_lines, warn_bad_lines, on_bad_lines, delim_whitespace, low_memory, memory_map, float_precision, storage_options) 584 kwds.update(kwds_defaults) 585 --> 586 return _read(filepath_or_buffer, kwds) 587 588 ~/anaconda3/envs/uc-python/lib/python3.9/site-packages/pandas/io/parsers/readers.py in _read(filepath_or_buffer, kwds) 480 481 # Create the parser. --> 482 parser = TextFileReader(filepath_or_buffer, **kwds) 483 484 if chunksize or iterator: ~/anaconda3/envs/uc-python/lib/python3.9/site-packages/pandas/io/parsers/readers.py in __init__(self, f, engine, **kwds) 809 self.options["has_index_names"] = kwds["has_index_names"] 810 --> 811 self._engine = self._make_engine(self.engine) 812 813 def close(self): ~/anaconda3/envs/uc-python/lib/python3.9/site-packages/pandas/io/parsers/readers.py in _make_engine(self, engine) 1038 ) 1039 # error: Too many arguments for "ParserBase" -> 1040 return mapping[engine](self.f, **self.options) # type: ignore[call-arg] 1041 1042 def _failover_to_python(self): ~/anaconda3/envs/uc-python/lib/python3.9/site-packages/pandas/io/parsers/c_parser_wrapper.py in __init__(self, src, **kwds) 49 50 # open handles ---> 51 self._open_handles(src, kwds) 52 assert self.handles is not None 53 ~/anaconda3/envs/uc-python/lib/python3.9/site-packages/pandas/io/parsers/base_parser.py in _open_handles(self, src, kwds) 220 Let the readers open IOHandles after they are done with their potential raises. 221 """ --> 222 self.handles = get_handle( 223 src, 224 "r", ~/anaconda3/envs/uc-python/lib/python3.9/site-packages/pandas/io/common.py in get_handle(path_or_buf, mode, encoding, compression, memory_map, is_text, errors, storage_options) 607 608 # open URLs --> 609 ioargs = _get_filepath_or_buffer( 610 path_or_buf, 611 encoding=encoding, ~/anaconda3/envs/uc-python/lib/python3.9/site-packages/pandas/io/common.py in _get_filepath_or_buffer(filepath_or_buffer, encoding, compression, mode, storage_options) 394 if not is_file_like(filepath_or_buffer): 395 msg = f"Invalid file path or buffer object type: {type(filepath_or_buffer)}" --> 396 raise ValueError(msg) 397 398 return IOArgs( ValueError: Invalid file path or buffer object type: <class 'list'>

That error is admittedly long, but it is informative:

ValueError: Invalid file path or buffer object type: <class 'list'>

It might be wise to have a test that makes sure our function raises a ValueError on CSV filenames.

@pytest.mark.parametrize(

'csv', [ ['a', 'b', 'c'], 123 ]

)

def test_bad_input_error(csv):

with pytest.raises(ValueError):

features, target = my_module.get_features_and_target(

csv_file=csv,

target_col='Sale_Price'

)

Here, we're testing two types of bad inputs: a list and an integer.

Then we're using with pytest.raises(): -- a context manager -- to make sure the code block inside of it raises the error we expect.

Raising good exceptions may seem unimportant at first glance, but an error is much better than bad input passing silently! That could lead to your project results be invalid. Maybe the output metrics are incorrect, or the model was trained on unreliable data.

If something is wrong, you want your code to error as earlier as possible.

Aside: Raising Your Own Exceptions¶

We don't have time today to go into raising exceptions, but it's possible to issue errors from your own code using

raiseYou might see something like:

if x < 0:

raise RuntimeError('Invalid value for x')

- This will halt the code in its tracks, propagating a RuntimeError, if `x` is less than 0.

Good Tests¶

- We've written quite a few tests, but what makes a good test? What's worth checking?

- Situations

- A very standard set of inputs

- Sets of inputs that are most likely to behave differently than others

- e.g. datasets with lots of NaNs, empty strings, file paths that don't exist

- Resulting actions

- Returning valid results

- Raising sensible errors

And various permutations of the above -- for each function you write.

Your Turn

Add a test for the make_preprocessor function to tests.py. It can be very simple. Rerun your tests.

Then parametrize it and run the tests again.

Wrapping Up¶

- In large projects, there are usually multiple files full of tests.

- Standard practice is to name them all

test_<something>.pyand keep them in atests/folder. - People have different methods of organizing their tests, but one test file per function of your code is a good starting point.

- Standard practice is to name them all

- pytest is extremely powerful and we touched on just a few of its features. I recommend Python Testing with Pytest if you want to learn more.

- Learning to write useful tests for your code is a journey. Creating tests is work, and you have to measure the value against the effort required.

- As a general rule, production code justifies many more tests than adhoc analysis projects. Shared code libaries need even more.

- You'll hear about various types of tests: unit, integration, smoke, and more.

- The only one to know right now is unit testing: tests for small chunks, or units, of your code. That's often the simplest starting point.

Your Turn

Add, commit, and push your project updates.Questions¶

Are there any questions before we move on?